How to Manage Disaster Relief Funds

24 March 2020

Emergency funds and the Stafford Act will impact every civic leader in our nation during the next weeks. We have prepared a series of educational videos, podcasts, white papers, workbooks, and other materials to help us all out. While the times may be uncertain, the facts of the 1988 Stafford Act are not. Historically 75% of fund recipients experience failure when managing these funds. Our promise is to improve the lives of the American public by assuring immediate, effective, responsible management of these grant funds.

My name is Christina Moore. Nine years ago, I had never experienced the anxiety nor understood the risks associated with this federal grant program. Then my community got hit by Hurricane Irene. Since that day to this, I have managed over $5 billion in FEMA funds. I’m a certified emergency manager, a former EMS Chief, critical care paramedic who was deployed to disasters in New York City, Puerto Rico, Florida, Texas, Vermont, and Connecticut.

Funds are Coming

That’s not the story we’ll tell years from now. Emergency funds come with specific legal obligations for the community leader, fire chief, mayor, local nonprofit director, EMS chief, police chief. These funds will flow into every sector of our civic life. If you have a civic job, work or volunteer for any organization that is responding to the COVID-19 emergency, these emergency funds will touch your lives. There are those who have not been scarred by experiences with FEMA monies and there are those who are scared of future interactions with emergency funds. Scared people and scarred people have an advantage over the newbies. The first step requires acknowledging that these funds are public. You are the steward of these funds even before you spend them. What do I mean? If you spend a dollar now that you think the emergency funds will reimburse you for, you must follow the federal rules today.

I have two immediate actions that civic leaders can take.

What to Know

The Stafford Act provides the United States federal government with the authorization to reimburse eligible parties for expenses related to nationally declared disasters. The law came into effect in the late 1980s and has helped millions of people in thousands of communities. Hurricane Katrina, the damage from the World Trade Centers, and the recent disasters in Puerto Rico to name a few, it has a broad scope. The core intent is to use federal funds and resources to help communities like yours return from the impact of disaster. The primary goal is restoration of essential services. The secondary goal is to improve resiliency when facing crisis. The emergency funds described in the news and in the law are grants, an entity such as the local fire department or library will be awarded a grant.

With a grant award, federal funds will be obligated, reserved equal to the grant award. When you accept the grant funds, you simultaneously accept the legal responsibility to follow the federal laws for grant management and for federal procurement. That information is never obvious upfront and it becomes clear weeks, months, or even years after you’ve spent the first dollar. Let’s avoid the oops. It’s easier than it appears. Think of it as a board game with rules. Play by the rules, step through the obstacles. Unlike a board game, managing emergency funds should have thousands of winners. Failure to follow the rules has serious impact.

Let’s Scare you for a Minute

The biggest risk we face when managing federal grant funds is the loss of that money. When you make a mistake today, seven years from now FEMA can come along and ask for that money back. There is a case of a nursing home in Colorado that received $11 million in 2013 following flooding. In 2020 the Department of Homeland Security found errors. Their published findings suggest that half of that money, $5.57 million be returned to FEMA. Now imagine being the administrator of that nonprofit nursing home. I’m confident that that facility does not have $5 million in their pocket. When this happens to towns, counties, and states, the risk is that there is a local tax increase.

The next biggest risk results from a paperwork issue that resembles fraud. If you do not follow the rules and somehow the federal government can prove that you or your family benefited, you may face felony fraud charges. Sometimes they don’t even need to prove that you benefited. If you intentionally bypass a step, you may have committed fraud. If you accidentally bypass a step, you may have just impacted the tax rates for your community for years to come.

Scared yet?

Do be a little scared all the time. Be respectful of the duty you have assumed. You have a legal obligation to be fair and open about the use of these funds. The funds may be used precisely for the purpose FEMA intends. If they give you funds to buy 100 masks for $100 and you buy magic beans that cure COVID instead, you’ve done wrong.

The Mechanics and Why it Matters

The funds originate with the US government with FEMA as the lead agency. The administration of the grant funds is done by a state agency. The state agency varies by state. And by the way, when I say state, I include the territories and districts of the United States. The term state is precisely defined in 2 CFR 200,90 and it bundles district of Columbia, Virgin Islands, Guam, et cetera, into the word state. 2 CFR 200 is the code of federal regulations that establishes a unified set of rules for federal grant management. States administer the funds on behalf of FEMA. The funds flow down. The local civic leader, you or your neighbor will be invisibly deputized to manage these funds.

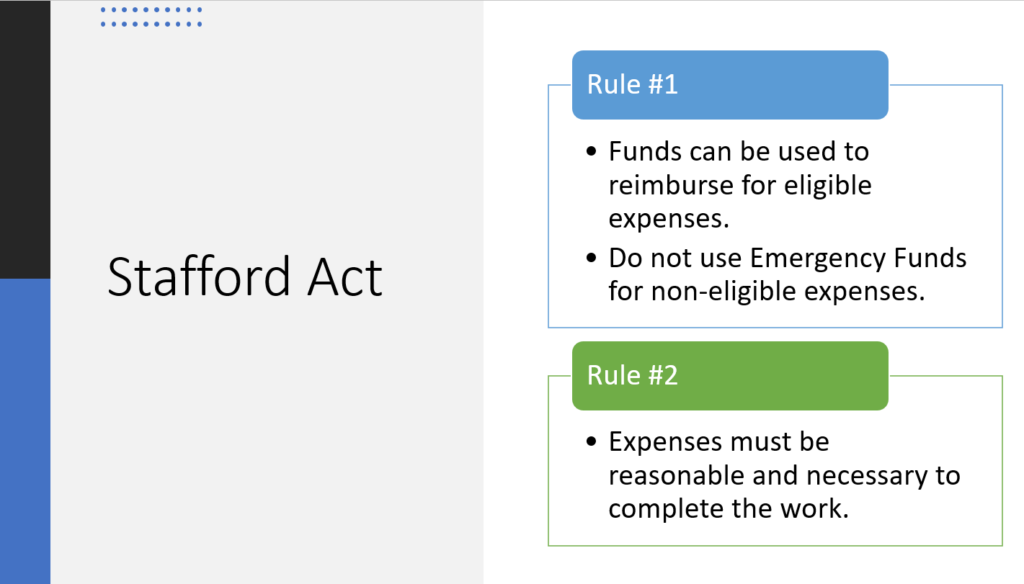

Stafford Act Rule #1

Funds can be used to reimburse for eligible expenses. You may not use emergency funds for noneligible expenses. Pretty basic stuff.

Stafford Act Rule #2

Expenses must be reasonable and necessary to complete the work. You are the steward of my tax dollars and they’re your dollars too. Each dollar spent must be for a necessary purpose and the cost must be reasonable.

One Plus Two Equals Action

From today on, or last week or last month, you have disaster specific expenses, but you also have to manage the basic everyday operations. Therefore, you need to identify what actions you and your team are taking that relates specifically to the disaster. You also need to identify what costs you and your team are encumbering while preparing and responding to this disaster.

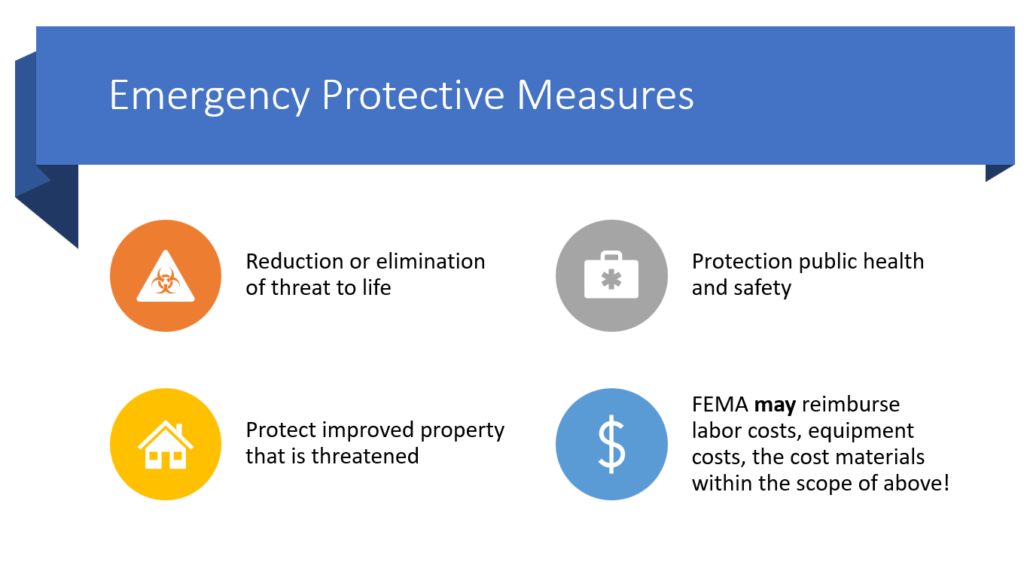

FEMA’s own rules of what will likely be considered for reimbursement include the following three. Tasks that we undertake to eliminate or reduce the threat to life, that’s one. Number two, protect the public health and safety. Number three, and protect improved property that is threatened. If your actions and related costs fall into these three categories and you happen to run a governmental or governmental-like entity, then your expenses in labor costs may be reimbursed by FEMA. FEMA may reimburse your labor costs, your equipment costs, and materials that you use or buy while providing emergency response given the rules above of course.

Actions

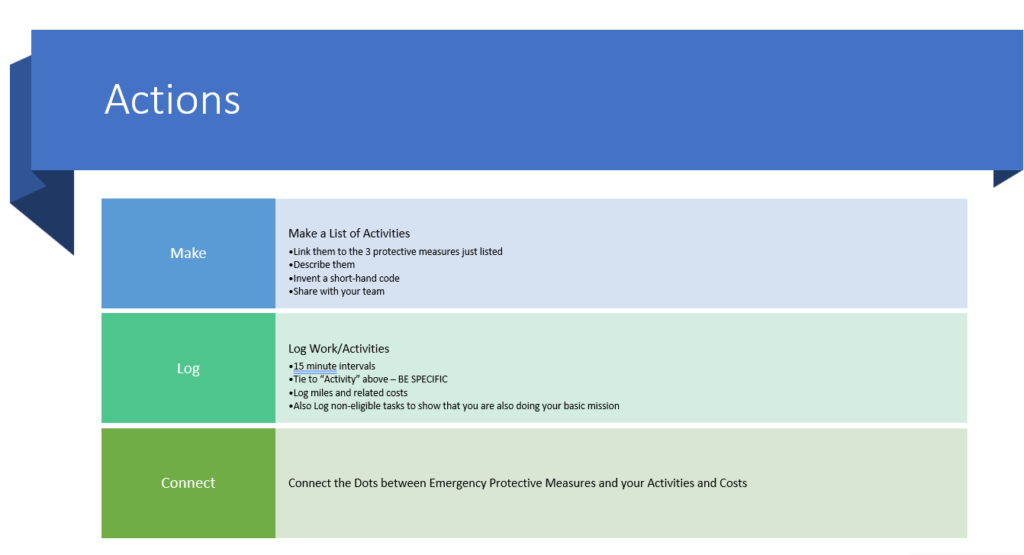

Make a list of actions and expense categories that meet the rules above. Be specific. Maybe your police department delivers food to isolated people during the crisis, that could be an eligible cost. You’ll likely get reimbursed for the miles the officer drove and the hours that the officer worked on that specific task. Responding to the car accident in the middle of that mission is not eligible. You report these differences with a very detailed paper log. Hey, if you have a sophisticated dispatch system or a task management system, then this is easy for you. For most teams, this is a burden. It is a pain in the anatomy, I get it. I’ve done it. Where’s the win? You have shifted community funded costs to a federally funded grant.

Action #1

Make a list of the activities your team is taking or plan to take that are related to the disaster and those three key principles. For example,

Task: Food, water delivery to those at risk.

Purpose: Reduce the threat to life by keeping people nourished.

You can give it a shorthand code if you’d like. It’s easier to write on a log.

Code: COVID food distribution.

Maybe you take on another task. Maybe you host an online community forum with social media and live video. The aim is to provide education on the management of mild cases of COVID and when to call for help with emergency services.

Task: Public health education.

Purpose: Protection of public health.

Add to this list as you need to. Collaborate with the team. Share it. Use it as a touchstone for the actions and the plans that you’ve got.

Action #2

Have a means of logging the activities to the nearest 15 minutes. It’s a super granular time sheet. Each line that is clearly linked to the reduction of threat of life, the protection of public health and safety, and the protection of at-risk property could be reimbursed by FEMA. The logs must be specific. Don’t just write COVID on a line. Link your time and expense to the activities identified in action number one. Connect the dots between the rules and the actions; you want to show that your action is possibly eligible and reasonable.